Case-study /

Planning for the future and adapting to climate change in Uganda – Lessons from ACCRA

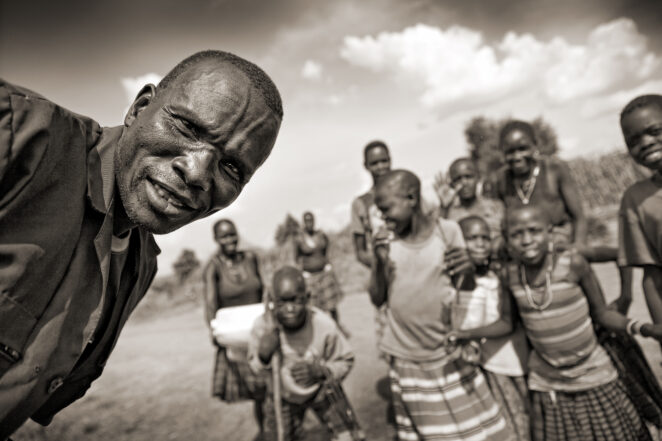

Community members supported by ACCRA’s work in Kotido district, Uganda

Adaptation context

Uganda is highly vulnerable to climate change due to its heavy dependence on rain-fed agriculture. Recently, erratic and unseasonal rainfall has cost the country over US$60 million in crop losses per year. Over 4 million people have been affected by disasters in Uganda since 1979, and more than 500,000 have died from disaster-related causes, while many others have been displaced from their homes.

Vulnerability to climate hazards, variability and change has been further exacerbated by poverty and inequality, high population, low levels of awareness, poor infrastructure, high rates of HIV/AIDS, and armed conflicts. Women in particular, are hit hardest, struggling to provide water and food for their families.

The Government of Uganda has implemented Disaster Risk Reduction and Climate Change Adaptation activities for a long time. It has signed up and ratified the Hyogo Framework for Action, the AU’s Africa Regional Strategy for DRR and others, as well as developing the National Disaster Preparedness and Management Policy and the National Adaptation Programme of Action. Whilst many efforts have been made, implementation of existing commitments at the local level is still a challenge.

Adaptation approach

ACCRA’s earlier work showed that policymakers face difficult trade-offs in planning for a changing and uncertain future. Yet many development actors continue to plan for the short term, with little room for manoeuvre or contingency. ACCRA therefore chose to focus on one specific characteristic of adaptive capacity in order to help decision makers improve planning and be better prepared for the future:Flexible and Forward-Looking Decision Making (FFDM).

As a concept, FFDM is relatively straightforward to understand. In practice, though, it is often hard to communicate and to relate to complex real-world problems. In collaboration with the abaci Partnership and the Red Cross/Red Crescent Climate Centre, ACCRA developed a ‘game-enabled reflection approach’ to promote FFDM. The game-enabled reflection approach was tailored for district-level planners and developed into a two- to three day workshop in Kotido District in the Karamoja region.

ACCRA has also raised awareness and trained in mainstreaming climate change adaptation into local government development plans and programmes, with training delivered to both district planners from Kotido and Bundibugyo Districts as well as consortium members. Training focussed on developing skills and knowledge in climate change capacity and vulnerability assessment tools, including the ACCRA LAC tools as well as gender analysis tools.

ACCRA is also strengthening weather forecast and climate information for local planning byworking with the MoWE Department of Meteorology to interpret and disseminate seasonal weather forecasts for use by farmers. This has involved translating weather forecasts into local languages, training staff in producing seasonal information and developing ‘questions and answers’ to dispel myths about meteorology.

Lessons Learned from our research

Although district development planning is decentralised, government spending be guided by the national priority sectors of roads, water, health, education and agriculture. While the district development process is designed to involve a wide range of stakeholders and to be holistic, in practice planning is limited to these five areas, and initiatives outside of these sectors are not supported. As the District Chairperson of Kotido explained at the outset of ACCRA’s involvement in Uganda, ‘we are not really in charge of our plans and budgets. Every Ministry sends its own guidelines.’

In Kotido, drought management and DRR are two important planning activities that are not funded by central government. While attempts have been made to create a structure for disaster preparedness and response at district level, with Kotido establishing a district disaster management committee, such activities must be funded from within the district itself, presenting a challenge to marginal areas like Kotido that have narrow tax bases and limited sources of revenue. Thus, little progress has been made towards planning for current and future risks.

What has ACCRA learned from having conducted 4 years of research and capacity building in Uganda? Below we described some of the key findings:

- Local and national plans are focused on the short-term. They often fail to take a long-term perspective and recognise future change and uncertainty. Decision making, even under normal circumstances, is a tough task. Add climate change-related uncertainties to it and it becomes even harder. Therefore, district-level decision makers need tools that help them deal with complexity in a flexible manner and allow them to consider potential future threats – climate-related or otherwise.

- Although communicating concepts such as uncertainty and FFDM can be difficult, a game-enabled reflection approach can help in communicating FFDM to development practitioners.But changing perceptions and institutional structures is a gradual process, requiring continuing support from development partners. Interventions delivered as a one- off and in isolation are unlikely to succeed. Successful and sustainable interventions will require considerable and well-timed investment.

- ACCRA’s approach has built momentum for change. As a result of capacity building thus far, consortium members have embarked on developing strategies for mainstreaming CCA and DRR at different scales, on revising programmes to address climate change issues, on moving away from the traditional disaster emergency response to integrated approaches with a view of supporting long term community resilience to climate change, and on fundraising for new climate related projects. However, the general feeling is that more skills and knowledge trainings are still needed.

- ACCRA’s experience in Bundibugyo shows that local governments can mainstream climate change and improve performance at the same time.By collaborating across sectors and harmonising activities, Bundibugyo outperformed in the annual national local government performance assessment and won a 20% bonus that increased its annual budget. This was also the basis why Bundibugyo was selected as one of four districts in Uganda to pilot the National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA).

- ACCRA’s capacity building is delivering results at the community level.Farmers using seasonal weather forecasts for the first time testify to have used this information in making informed decisions e.g. opting for different crops and/or building irrigation canals in preparation for long rains. Both women and men access this information in different ways, which has helped stakeholders to target women as well.

Recommendations

To enhance adaptive capacity and promote FFDM, many different actors will need to take action. ACCRA recommends that the following activities be instigated:

District governments should exploit opportunities to promote FFDM within constraints by:

- Integrating CCA and DRR into district level plans. For example, in Kotido District, the development plan is being updated‘[…] to accommodate all crosscutting issues, including climate change. Before the ACCRA training, climate change was not directly catered for in the district plans but now it is there. This is because of awareness by ACCRA.’ (Clerk to Kotido).

- Making better use of available information. For example, the Kotido Natural Resources Department is disseminating weather forecast information across sectors. According to a senior education officer, ‘now [weather forecasts] come monthly. It used to come to specific people and quarterly. The Chief Administrative Officer has made it a necessity for them to be disseminated to all local officials.’

- Seeking information and advice from external sources. Advice on vulnerabilities, for example, is being sought more often from NGOs since the ACCRA workshop and capacity building. When capacity building in Kotido uncovered that the existing district plan did not meet national minimum standards, the district authorities and ACCRA invited staff from key ministries to help the district develop its plan.

- Collaborating across and within different sectors and districts to pool resources and draw up contingency plans. For example, Bundibugyo district, with ACCRA’s support, worked to strengthen local public planning and integrate gender-sensitive CCA and DRR. This resulted in an integrated district development plan, much higher levels of community participation, and better central and local government connections.

- Reflecting on where the district aims to be on time horizons beyond the traditional three-to-five-year planning cycles.

- MoWE and OPM with ULGA should encourage and support districts to develop longer-term strategies that incorporate principles of FFDM and lobby for adequate resources to support the plans.

- Districts should be given flexibility to define and shape their own development targets based on local needs and priorities. For example, ACCRA helped to establish closer links between Kotido District and key Ministries.

- Greater coordination across sectors and ministries, including MoWE, OPM, ULGA and the Climate Action Network -Uganda, and between different levels of government should be promoted.

Non-governmental and civil society organisations should incorporate the principles of FFDM into their own policy and practice by:

- Using local evidence to influence policies, programming and practice at national, regional and global levels.

- Mobilising technical and financial resources to promote ongoing dialogue around FFDM. For example, Oxfam provided financial support for a workshop between district authorities and key ministries to support the process of updating district development plans.

- Promoting collaboration across sectoral boundaries. For example, in ACCRA’s engagement in support planning in Kotido, different sectors units were able to come together and ensure that the plan was harmonised and cross-cutting. Initially each sector planned in isolation.

- Bringing together stakeholders across levels of governance. For example, ACCRA is implementing an advocacy strategy to involve the regional IGAD- Climate Prediction and Application Center in ensuring that the Government of Uganda prioritises and funds this activity in the future. The first national conference with IGAD involvement was held in November 2013 and the IGAD representative exhibited interest in the innovation and promised to share with the World Meteorological Organization (WMO).

Donors and multilateral agencies need to ensure they are responsive to changing priorities and unforeseen circumstances by:

- Enabling greater flexibility by moving away from target-based thinking to look for beneficial outcomes in the longer term.

- Adjusting funding timescales to provide incentives to consider and promote longer-term objectives within projects and programmes.

- Learn about ACCRA’s experience in Mozambique

- Learn about ACCRA’s experience in Ethiopia

- Planning for an uncertain future: promoting adaptation to climate change through Flexible and Forward-looking Decision Making

http://weadapt.org/placemarks/maps/view/1187

- Blog – When Kotido District Local Government appreciated Flexible and forward looking decision making

- Video – when district officials played the ACCRA game, Kotido district, Uganda

ACCRA Uganda

ACCRA in Uganda is a consortium made up of Care International, Oxfam, Save the Children, and is led by World Vision Uganda. Key government actors include: the Office of the Prime Minister-OPM (Department of Disaster Preparedness and Management); the Ministry of Water and Environment (MoWE) (Department of Meteorology and the Climate Change Unit); the Uganda Local Government Authority (ULGA); the Parliamentary Forum on Climate Change; and the Climate Change Action Network (CAN-U).