Case-study /

INSIDE STORY: Supporting the subnational development of renewable energy – Lessons from West Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia

Introduction

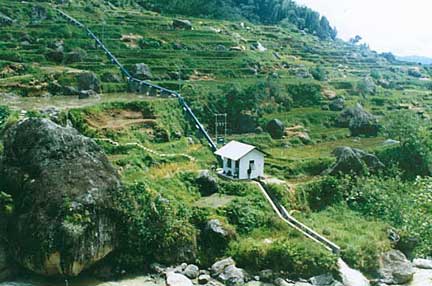

West Nusa Tenggara is a major tourism destination in Indonesia because of its rich seascapes and landscapes as well as its unique culture. However the region faces severe energy shortages. Across the province’s 10 districts and municipalities, electricity supply is lacking because of limitations in grid connections imposed by difficult geography and high costs. This lack of energy limits economic development in the area and contributes towards social vulnerability because it inhibits community access to basic technology such as lighting and heating/cooling facilities. However, there is great potential for renewable energy: more than 96.5 MW could be made available from mini-hydro schemes alone. That compares with an existing total capacity (on-grid and off-grid) from renewable energy of only 14 MW, according to 2015 data.

This CDKN Inside Story* discusses the policy recommendations made as part of the Migration Momentum project, funded by the Dutch and German governments, to developing renewable power capacity in Indonesia by independent power producers (IPPs). The story focuses on the implementation of micro- and mini-hydro power systems, and draws from interviews with IPP representatives and other stakeholders to discuss the institutional framework for renewable development and give considerations for decision makers.

*download this CDKN Inside Story from the right-hand column or via the links available under further resources. Barriers, enabling factors, implications for decision makers and key messages are summarised below; please see the full text for greater detail.

Barriers

The basic message from potential IPPs to policy-makers is that mini-hydro development is impeded not just by technical aspects but by governance issues as well.

- Land acquisition is subject to local dynamics. The price of land may rise rapidly when local communities learn that a project is or may be coming their way. This may be remedied by either not disclosing pinpointed potential project sites, or even better involving communities proactively at the earliest plannig stages.

- Information on land type is not always accurate. Accurate maps and participatory mapping excercises are both needed if conflicts over use and tenure and consequent delays to the acquisition process are to be avoided.

- Asset transfer can be slow. Projects cannot progress until the assets they require have been transferred. Asset transfer is often slow since detailed appraisal by the Ministry of Finance is needed before the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources can transfer to the district/municipality government.

- On- and off-grid supplies are sometimes poorly coordinated. If appropriate subnational regulations were in place, the role of the state electricity company, PLN, could be better coordinated with that of small-scale cooperatives and IPPs, avoiding overlaps in grid expansion with off-grid developments.

- Permit application process is not user-friendly. The process and its costs should be made more sensitive to the needs of small scale IPPs, which must keep costs and timescales reasonale if they are to remain viable over time. The permit process could be streamlined.

Enabling Factors

The study revealed a number of enabling factors, including a gradual improvement in the design and implementation of the regulatory framework. For instance, the provincial Governor’s Regulation No. 12/2015 regarding protocols for licensing in the fields of new and renewable energy and electricity helped clarify the procedures for IPPs, and at the same time improved coordination between provinces and districts and/or municipalities. This can improve energy planning, as well as broader development plans and implementation.

Implications for Decision Makers

Policy considerations

- Identifying the right level for intervention. The study identified that the provincial level is the appropriate starting point, particulalry since the decentralisation process started in 2014. All stakeholders will need to keep abreast of future legislative changes resulting from Indonesia’s complex national dialogue on decentralisation.

- Ensuring harmonisation of plans. Cross-sectoral coordination could be made more effective, for example by harmonising the law relating to land tenure in the energy sector with that relating to watershed management.

- Ensuring consistency in targeting. Provincial plans for electricity should state power generation targets that comply with the existing, clear targets for emission reduction, and try to be in line with climate adaptation strategies.

- Resolving regulatory contradictions. Varying individual capacities of legislators and staff in executing agencies give rise to differing policies and interpretations. This calls for continued capacity building and dialogue facilitation by relevant agencies and advocacy on the part of civil society, including academia and media, as well as institutionalised multi-stakeholder approaches.

Institutional arrangements

- Ensuring buy-in at all levels. Even when there is high awareness and commitment to a local action plan at the provincial level, buy-in from districts and/or municipalities is still necessary. Social acceptance of the new technology is also very important. West Nusa Tenggara’s ten districts and municipalities scarcely had their own version of the local action plan, detailing action at their level.

- Capacity building in IPPs. IPPs need to develop capacities to design projects that meet the technical and financial standards required by the state electricity company, PLN, and the banks. Training centres are an underused resource in this respect.

-

Strong and continuous support from heads of provinces. Heads of provinces should continue to mobilise multi-stakeholder approaches and the involvement of local communities. A provincial Multi-stakeholder Energy Forum was effective from 2005 to 2013, but the much needed local budget support assigned to the provincial office of energy and mineral resources from the provincial planning board was withdrawn. Such institutionalised mechanisms at the provincial level would be worth revitalising to foster capacity, ownership and social acceptance.

Financing

- Subnational entities won’t necessarily lack finance. Indonesia’s recent move away from fossil fuel subsidies means more funds should become available for renewables. Furthermore, beginning with the Yearly Budget Plans 2015, the country’s new village governance law bestows top-up funds of close to US$750,000 per village to each of Indonesia’s 72,000 villages. This means that many provinces will have the financial resources needed to support climate compatible development, alongside infrastructure as the main competing demand.

- Coordinating budgets and plans across villages will increase feasibility. Neighbouring villages could put their heads together and set aside, say, 5% of the funds allocated in their Yearly Budget Plans for renewable energy infrastructure. For example, Lombok Barat District alone has 122 villages and not all of these will need their own renewable energy projects. Indeed, the need for economies of scale will dictate collaboration across locations.

- Regional banks could deploy additional resources. Provincial development banks often hold funds that need to be disbursed. For example, Regulation No. 5/2007 of the Ministry of State Owned Enterprises requires private companies to set aside 2% of their profits for environmental management and community development activities. This money could be used to build the capacity of local businesses and communities to support and develop local technological solutions.

- Other measures to ease financing include the reduction of import duties on parts such as turbines and generators, and waiver of the tax on surface water use for electricity generation.

Key Messages

- Mainstreaming energy security in climate compatible development (accounting for climate mitigation and adaptation goals) calls for delicate policy and institutional reforms, which in turn call for a PPPP approach: Public–Private–People Partnership.

- Sound policy-making at the provincial government level calls for continual capacity building. Also needed are multi-stakeholder participatory approaches and advocacy on the part of civil society.

- Effective enabling policies and strategic coordination on key issues can provide incentives for local power generation. A key issue in West Nusa Tenggara is the balance between on-grid and off-grid electricity.

- Community-level producers are vital and need to be motivated differently from commercial ones (i.e. need for tailored incentives).

- Mini-hydro electricity generation cannot be separated from forest conservation, particularly if considering climate mitigation and adaptation synergies, so an approach to spatial planning that integrates these two objectives is critical.

Authors and Funding

Mochamad Indrawan (CDKN), Rosmaliati Muchtar (Universitas Mataram), Lachlan Cameron (Energy Research Centre of the Netherlands) and Niken Arumdatin (Provincial Government, West Nusa Tenggara)

The report: “Supporting the subnational development of renewable energy: Lessons from West Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia” is an output from a project commissioned through the Climate and Development Knowledge Network (CDKN). CDKN is a programme funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) and the Netherlands Directorate-General for International Cooperation (DGIS) for the benefit of developing countries.

Suggested Citation

Indrawan, M., Muchtar, R., Cameron, L., Arumdatin, N. 2016. Supporting the subnational development of renewable energy: Lessons from West Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia. INSIDE STORIES on climate compatible development. Climate & Development Knowledge Network: London, UK.

View this Inside Story on CDKN’s website here

Other CDKN inside stories – http://cdkn.org/cdkn_series/inside-story/

Information on the Inside Story project – http://cdkn.org/project/inside-stories-on-climate-compatible-development/