Case-study /

When is migration a maladaptive response to climate change?

Introduction

Climate change affects rainfall variability and food security, in some cases leading to migration. Improved understanding about the interactions between climate and food security is needed before we can determine whether migration is a truly adaptive response in poorer countries. Without this understanding, it is difficult to design effective strategies that ensure climate resilient development.

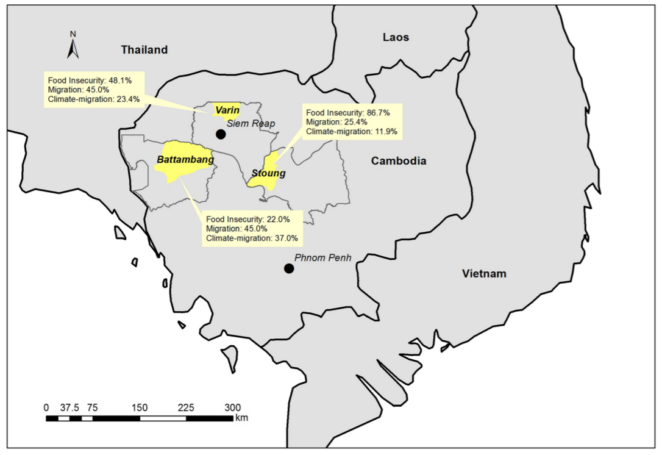

This paper* presents an analysis of climate, food security, migration, and its consequences from 218 households in three locations in North-western Cambodia, the most climate vulnerable nation in SE Asia.

This open access paper was originally published in Regional Environmental Change in January 2019 (first online: 28 July 2018).

*Access the full paper using the featured download in the right-hand column or by following this link. A summary of keys sections of the paper is provided below.

Methods and Tools

This study sought to understand whether migration was adaptive or maladaptive by addressing the following questions:

- How is the climate changing?

- What rates of migration exist and what are the drivers of it?

- What are the consequences of migration for remaining communities?

Case study locations

Lvea Krang (Varin District) is a remote subsistence community in the foothills of Kulen Mountain, equidistance between the Siem Reap and the border at Anlong Veng. There is no power or running water, and key crops include rice and cassava.

Popok (Stoung District) is a remote community but one with power and water and diversified livelihoods including rice, cassava, and cashew nuts.

Chamkar Samrong is a peri-urban community on the outskirts of Battambang City, with only 30% land in agriculture production (rice and some fruit trees); many residents work in the city, or own agricultural lands in the surrounding district.

Climate change

This study analysed climate change trends by comparing patterns in MODIS-derived normalised difference vegetation index (NDVI), at the district scale.

Migration, its drivers and consequences

Survey data was collected from 10% of households in each community, sampled using a systematic random design using every 10th household from each village.

- Descriptive statistics are reported, comparing households with and without migrants.

- For migration causes, four specific response groupings were created:

- (1) food insecurity;

- (2) ‘climate related’, including bad harvest, agriculture, and natural disaster;

- (3) ‘economic’, including debt and income; and

- (4) other.

Key findings

Climate change

- NDVI (2000–2016) analysis shows a trend towards drying.

- Trends also show increased variation in the number of abnormally wet months per year, and in the number of abnormally dry months per year.

- Results indicate that 2015/2016 was abnormally drier in both Battambang and Stoung districts, but not in Varin.

- According to FAO, WFP, and UNICEF, 2015/ 2016 was the most significant drought in the past 50 years in Cambodia, and these results concur with this.

The drivers and consequences of migration

- In all communities, most primary migrants (58.3–75.0%) were men, younger (average ages between 22.5 and 25.2 years old), and displaced for between 7.8 and 9.5 months per year.

- Secondary migrants were more commonly women (72.7%, 66.6%, and 44.0%), between 21.2 and 23.6 years old, and displaced for 6.0– 10.0 months per year. Popok.

- Remittances from primary migrants varied, averaging $307–$834 per annum depending on location, with higher remittances from communities closer to the Thai border.

- Averaged secondary migrant remittances varied from $604–$687 per annum.

- Given the interconnectedness of economic and climate-related reasons, and that climate-related issues are less apparent to community members, additional analysis was conducted removing climate-related reasons from economic reasons where both were identified.

- In doing so, climate-related reasoning becomes more prominent, particularly in communities where migration is highest.

- The biggest impacts of migration were perceived to be:

- labour shortages (50.0% households in Lvea Krang, 40.0% in Popok, and 6.5% in Chamkar Samrong),

- child welfare-related concerns (50.0% of households in Lvea Krang, 34.7% in Chamkar Samrong, and 13.3% in Popok), and

- female safety (28.2% households in Chamkar Samrong, 13.3% in Popok, and 7.0% in Lvea Krang).

- These findings suggest that migration may not necessarily address climate-induced food insecurity.

- Climate-related impacts such as bad harvest and agricultural and natural disasters that induce food insecurity and debt explained between two-thirds and all of economic reasons for migration, making ‘climate-related’ factors a key migration driver.

- Patterns of migration across the year are important given that they influence the ability of a community to avoid impacts on critical production events.

Implications for adaptation

- Communities are at or below the economic threshold at which migration is ‘survival’ oriented.

- The climate is becoming increasingly unpredictable, increasing exposure to economic risk.

- Climate is the most significant driver of migration.

- The gendered and temporal nature of migration is causing socio-demographic shifts in remaining communities that impact on food insecurity.

- Sensitivity to food insecurity is increased due to:

- (a) gendered roles in agriculture,

- (b) the gendered nature of agriculture extension, and

- (c) cultural implications of adaptation activities that reduce exposure sensitivity.

- Climate change appears to be holding households in a cycle of food insecurity and migration. Addressing these issues requires consideration of adaptive capacity.

Lessons Learnt

- This study identified a clear pattern of climate-reinforced poverty trap, whereby climate related changes affect food insecurity, leading to subsequent migration that does not necessarily alleviate food insecurity, but leads to a range of social consequences.

- Migration appears survivalist at best and may, given climate projections, prove itself to be maladaptive response to climate change.

- Much greater concerted attention is needed to address the nexus between poverty and climate adaptation, including longitudinal understanding about the interactions between climate, debt, and food security.

- Differentiated adaptation strategies could avoid maladaptive pathways over the long term, and ensure migration does not remain a poverty trap.

Suggested citation

Jacobson, C., Crevello, S., Chea, C. and Jarihani, B., 2019. When is migration a maladaptive response to climate change?. Regional Environmental Change, 19(1), pp.101-112.

Further reading

- Migration as adaptation? A comparative analysis of policy frameworks

- When do households benefit from migration? Insights from vulnerable environments in Haiti

- Migration, Environment and Climate Change: Evidence for Policy (MECLEP)

- TransRe – Building resilience through translocality. Climate change, migration and social resilience of rural communities in Thailand

- Relocation as an adaptation strategy to environmental stress: Lessons from the Mekong River Delta