Article /

A guide to Effective Collaboration and Learning in Consortia

Introduction

Working in the complex context of climate change adaptation and resilience, individuals and organisations are often required to work together in consortia across disciplinary, institutional, geographical, and cultural boundaries. To learn more about what resilience really means, what it means within the context of cities, and more specifically, what does it mean for African cities, read this article.

This is a guide on how to effectively collaborate and learn in consortia, which helps to establish transdiciplinary learning processes and co-production of knowledge with a diverse range of stakeholders. Read more about the principles of transdisciplinarity, co-production and co-exploration here.

The text below provides an overview of the guidebook. See the full text for more detail.

How to use this guide

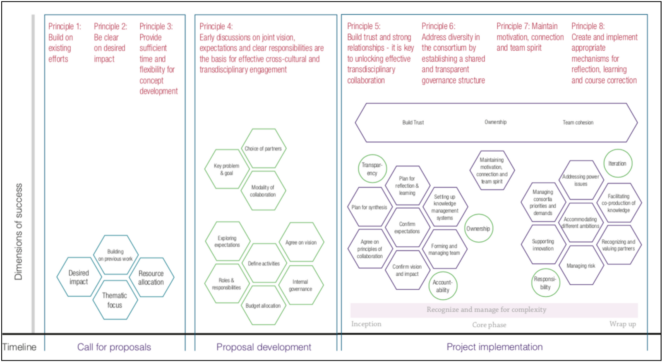

The guide is structured along a timeline of a consortium-based programme. It starts with a call for proposals and ends with the conclusion.

The guide highlights eight significant principles, each with a brief checklist of questions that encourage reflection on the process.

It also includes a range of examples from practice and thoughts from consortium members with real-life stories of challenges or successes contributing to learning in this community of practice.

Principles of Good Practice

Principle 1: Build on existing efforts – The definition of a clear thematic focus for the call for proposals is critical and will allow a programme to align more closely with existing initiatives.

Principle 2: Be clear on desired impact – A programme’s desired impact should be the key determinant of its length and this will depend on whether its core focus is implementation, research or policy influence. Funders often expect outcomes and impacts in all three areas.

Principle 3: Provide sufficient time and flexibility for concept development – Calls for proposals often have rigid requirements with respect to the selection of partners, the timing and modality of putting a proposal together, and the way budgets are determined and allocated.

Principle 4: Early discussions on joint vision, expectations, and clear responibilities are the basis for effective cross-cultural and transdisciplinary collaboration –Composing a consortium team and drafting the initial proposal is a delicate process, which requires collective attention and agreement on a number of matters. Ideally this should happen face to face.

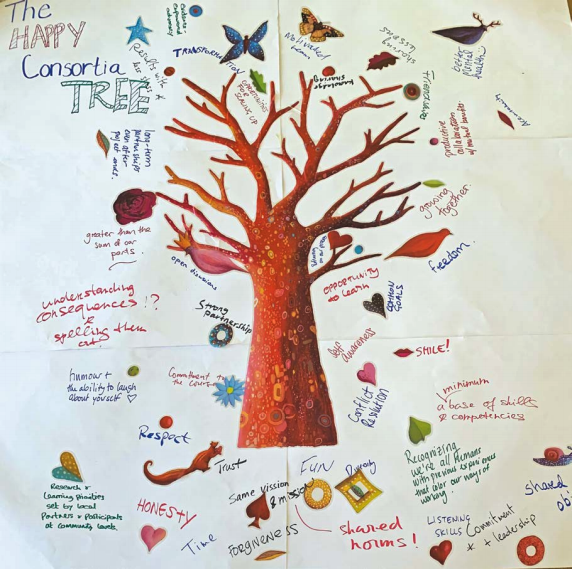

Principle 5: Build trust and strong relationships – it is key to unlocking effective transdisciplinary collaboration – Establishing a sound team, based on trust, ownership, and team cohesion, is one of the most important investments that one can make at the beginning of a project, particularly if new partners that have not worked together before are involved. Formal and informal activities that contribute to such aims are critical.

Principle 6: Address diversity in the consortim by establishing a shared and transparent governance structure – Agreeing on the internal governance system and principles of collaboration in a transparent, collaborative way is critical to establish a shared modality of working together synergistically. It is important to discuss how decision-making will be undertaken, responsibilities shared, accountability and transparency ensured, processes of reflection and learning integrated, etc.

Principle 7: Maintain motivation, connection, and team spirit – If insufficient time and attention have been dedicated to building relationships and to agreeing on a transparent governance structure, clear joint vision, objectives, overall framework, activities and workplan, consortium members may feel lost about what the project intends achieving and how they are meant to contribute. This may lead to frustration and a feeling of disconnect in the team.

Principle 8: Create and implement appropriate mechanisms for reflection, learning, and course correction – Regular reflection and learning sessions allow team members to explore challenges and to jointly decide on course corrections and adaptive programming. Ensure that the governance structure of the consortium allows all team members to voice their frustration or surface tensions.

Wrapping Up and Documenting Learning

Once the consortium comes towards the end, it is important to focus on its legacy, including the project outputs/deliverables and their impact.

It is also useful to take stock of what the consortium has learnt about collaborating and learning in consortia – the meta-learning of the project.

This meta-learning can support the wider community and individuals to actively consider lessons from past programme(s) and how to improve approaches and systems in a new consortium for improved learning and greater transdisciplinary impact.

If the consortium managed to actively reflect and learn, implement adaptive programming, and ensure sound knowledge management while engaging with the wider communities of practice, most of the work has been done when reaching this stage. It is then useful to think strategically about sharing these insights and further improving the practice of planning for and implementing consortia in complex contexts.

Suggested Citation

Koelle, B., Scodanibbio, L., Vincent, K., Harvey, B., van Aalst, M., Rigg, S., Ward, N. and Curl, M. (2019). A guide to Effective Collaboration and Learning in Consortia. London.

- FRACTAL: Future Resilience for African Cities and Lands

- CARRIA: Collaborative Adaptation Research Initiative in Africa and Asia

- PLACARD: Platform for Climate Adaptation and Risk Reduction

- Partners for Resilience

- SHEAR: Science for Humanitarian Emergencies and Resilience

- BRACED: Building Resilience and Adaptation to Climate Extremes and Disasters

- UK Aid

- Building Resilience in African Cities: A Think Piece

- Transdisciplinarity, co-production, and co-exploration: integrating knowledge across science, policy and practice in FRACTAL

- Climate Risk in Africa: Adaptation and Resilience