Article /

Toolkit for a Gender-Responsive Process to Formulate and Implement National Adaptation Plans (NAPs): Supplement to the UNFCCC Technical Guidelines for the NAP Process

Introduction

The impacts of climate change are not gender-neutral. Consequently, responses to these impacts, whether at the policy level or on the ground in vulnerable communities, must be gender-responsive.

The National Adaptation Plan (NAP) process is a key mechanism for defining adaptation priorities, channelling resources and implementing adaptation actions. It therefore presents a key opportunity to address the gender dimensions of climate change if it is undertaken in a gender-responsive manner.

This toolkit—a joint publication of the NAP Global Network, the Least Developed Countries Expert Group (LEG) and the Adaptation Committee under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)—is designed to support country efforts to pursue a gender-responsive NAP process. It will be useful for government actors coordinating the NAP process, as well as for stakeholders and development partners supporting adaptation planning and implementation. The toolkit offers a flexible approach, recognizing that there are opportunities to integrate gender considerations regardless of where you are in the NAP process.

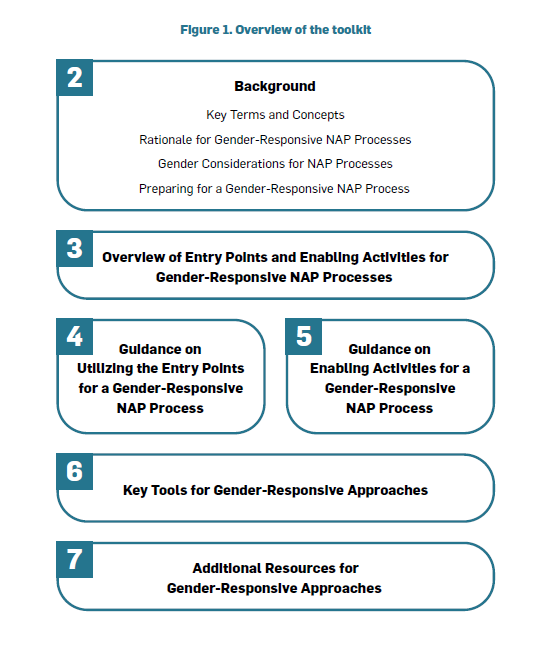

It is organized around the key entry points in the NAP process, based on the elements outlined in the UNFCCC Technical Guidelines for the NAP Process produced by the LEG. It also provides guidance on addressing gender in the enabling activities that facilitate progress and increase effectiveness in the NAP process, including the establishment of institutional arrangements, capacity development, stakeholder engagement, information sharing and securing finance.

* Download the full text (see right-hand column) for more detail. A short overview of the toolkit is provided below.

About the Toolkit

The urgency of investing in adaptation to climate change has never been clearer. Responding to the challenge of adaptation will require unprecedented coordination, collaboration and action among a range of actors in every country around the world. It will also require robust, forward-looking planning processes that consider the differential risks, vulnerabilities and capacities of different countries, communities and groups.

Under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the process to formulate and implement National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) was established under the Cancun Adaptation Framework in 2010 as a means of identifying medium- and long-term adaptation needs and developing and implementing strategies and programs to address those needs. Its importance is reiterated in the 2015 Paris Agreement. The objectives of the NAP process are to reduce vulnerability to climate change and facilitate the integration of climate change in national development planning across sectors and levels of governance. The guiding principles set out for the process highlight the need to integrate gender and to take into consideration vulnerable groups, communities and ecosystems. The NAP process is a critical vehicle for driving adaptation investments and ensuring that they are used effectively and targeted where they are needed most.

The impacts of climate change are not gender-neutral. Consequently, responses to these impacts, whether at the policy level or on the ground in vulnerable communities, must be gender-responsive. Indeed, the Paris Agreement refers to gender-responsive approaches, as well as to the goals of gender equality and empowerment of women. Furthermore, the establishment of the UNFCCC Gender Action Plan (GAP) has demonstrated parties’ commitment to addressing gender by providing a framework for gender-responsive climate policy and action.

The NAP process is a key mechanism for defining adaptation priorities, channelling resources and implementing adaptation actions. It therefore presents a key opportunity to address the gender dimensions of climate change if it is undertaken in a gender-responsive manner. Adopting a gender-responsive approach to adaptation will also help to align climate policies and action with other commitments, including the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action and the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW).

This toolkit—a joint publication of the NAP Global Network, the Least Developed Countries Expert Group (LEG) and the Adaptation Committee under the UNFCCC—is designed to support country efforts to pursue a gender-responsive NAP process. It will be useful for government actors coordinating the NAP process, as well as for stakeholders and development partners supporting adaptation planning and implementation. The toolkit offers a flexible approach, recognizing that there are opportunities to integrate gender considerations regardless of where you are in the NAP process. It is organized around the key entry points in the NAP process, based on the elements outlined in the UNFCCC Technical Guidelines for the NAP Process produced by the LEG. It also provides guidance on addressing gender in the enabling activities that facilitate progress and increase effectiveness in the NAP process, including the establishment of institutional arrangements, capacity development, stakeholder engagement, information sharing and securing finance. The toolkit also provides links to key tools for gender-responsive approaches, as well as other useful resources.

Considerations for a Gender-Responsive NAP Process

A gender-responsive approach to the NAP process addresses gender differences, promotes gender equality and actively challenges the biases, behaviours and practices that lead to marginalization and inequality. It recognizes that gender intersects with other socioeconomic factors to influence vulnerability to climate change and adaptive capacity. A gender-responsive approach increases the likelihood that adaptation investments will yield equitable benefits for people of all genders and social groups, including those who are particularly vulnerable.

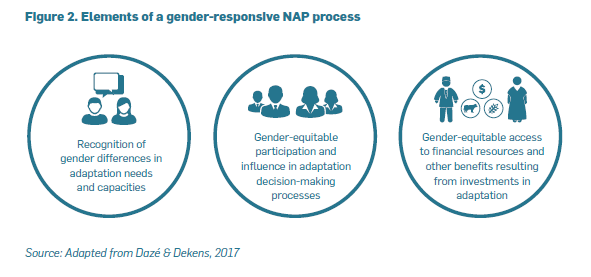

A gender-responsive NAP process focuses on three key considerations (see Figure 2).

RECOGNITION OF GENDER DIFFERENCES IN ADAPTATION NEEDS AND CAPACITIES

It is well established that gender influences people’s vulnerability to climate change. Gender intersects with other factors such as age, race, ethnicity, disability, class and sexual orientation to shape people’s socially determined roles and responsibilities and their degree of marginalization in society. These interconnected factors also influence people’s access to resources and information, their opportunities and their aspirations. Collectively, all of these issues affect the ability of different people to adapt to the impacts of climate change. These dynamics play out at multiple scales, including household, community and beyond, yielding differing adaptation needs and capacities for people of different genders and social groups.

Differences in adaptation needs stem from a number of different realities. First, the way people experience the impacts of climate change will differ depending on the roles they play in their households and communities. For example, in agricultural communities in Ethiopia, research has shown that women tend to be engaged in subsistence farming while men are typically involved in commercial farming and livestock rearing. This means that they are affected differently by events such as droughts: women may struggle with increased food insecurity and associated health impacts within the household, while men are confronted with impacts on their income and/or herd size, both of which are closely tied to their ideals of masculinity. Women’s unpaid household responsibilities, which can increase due to climate-related hazards and changes, may negatively affect their ability to engage in adaptation actions. Women may be more exposed to the risk of gender-based violence during times of scarcity or when they are displaced by natural disasters.

In assessing adaptation needs and capacities, it is critically important to recognize the differences between women and men—and how gender intersects with other socioeconomic factors as outlined above. Generalizations that position women at large as a particularly vulnerable group obscure these differences and overlook the complementarity of diverse knowledge types and women’s potential as agents of change. They also miss the dynamic nature of both gender norms and adaptive capacity and may reinforce gender stereotypes. A more nuanced, evidence-based approach is needed for adaptation to be genuinely gender-responsive.

GENDER-EQUITABLE PARTICIPATION AND INFLUENCE IN ADAPTATION DECISION-MAKING PROCESSES

People have a right to participate in decisions that affect them, their families and their communities. This is recognized in the Paris Agreement and other decisions under the UNFCCC that emphasize human rights and establish principles of participation and transparency in climate action. However, in reality, many people, particularly women and people in marginalized groups, face barriers to participation in decision making, from the household level to national policy making. This has implications for gender equity in participation and influence in adaptation decision-making processes.

At the institutional level, women remain under-represented in decision making in areas relevant for adaptation. Analysis of 193 countries found that, in 2015, women accounted for only 12 per cent of heads of environment-related ministries (including environment, water, agriculture and forestry, among others) and that 65 per cent of the countries analyzed did not have a single female minister. The World Bank has reported that less than 30 per cent of senior positions in the public sector are occupied by women . The obstacles to equal participation include legal and institutional barriers, access to education and cultural norms and practices. Similarly, in the private sector, women remain the minority in senior management.

Ensuring gender-equitable participation and influence and promoting female leadership at all levels in the NAP process will begin to redress the historical exclusion of women in decision making, in line with commitments such as CEDAW, the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, and the SDGs. This requires particular attention to the representation of marginalized groups, in addition to achieving gender balance, to ensure that differences among women and men are captured. Involving more diverse voices increases the likelihood that gender issues will be addressed in adaptation decision making.

GENDER-EQUITABLE ACCESS TO FINANCIAL RESOURCES AND OTHER BENEFITS RESULTING FROM INVESTMENTS IN ADAPTATION

The NAP process will channel resources to institutions and communities to implement adaptation actions. If done in a gender-responsive manner, this can serve to address inequalities while also enhancing adaptive capacities. This requires concerted action to tackle the persistent gender gaps in access to education, services, technologies and financial resources, ensuring that these are not reinforced or exacerbated by adaptation investments.

Although progress has been made, females still have less access to education than their male counterparts, with the gap widening as the level of education increases. Women are much more likely to be illiterate, particularly in least developed countries such as Chad, where the literacy rate for women is only 14 per cent, less than half of that for men. Similarly, when it comes to services, women are often at a disadvantage. For example, women tend to have less access to agricultural extension services due to the design of the services, household responsibilities or a lack of recognition that they are farmers, among other factors. Access to technologies, such as mobile phones, also differs for women and men. Recent data from low- and middle-income countries shows that women are 10 per cent less likely than men to own a mobile phone (rising to 28 per cent in South Asia) and 23 per cent less likely to use mobile Internet. Reasons include affordability, literacy and digital skills.

The income gap between women and men remains significant. For example, in countries such as Cambodia, the average earned income for a woman is only 73 per cent of that for a man. Recent global analysis by the WEF suggested that “economic power is still typically in the hands of men, who remain a household’s primary economic reference point, often maintaining control of financial assets, although women may have indirect influence on consumer spending.” Women have poorer access to financial services, with 9 per cent fewer women in developing economies holding an account at a financial institution. Women in rural areas face particular challenges in accessing financial services.

All of these factors influence the ability of women, particularly those who are poor or from marginalized groups, to capitalize on opportunities that arise through investments in adaptation. With less access to technologies, services and financial capital, women face additional barriers to participation in adaptation actions. Gender-responsive NAP processes acknowledge these gaps and target investments accordingly, with the aim of equitable benefits across genders and for marginalized groups. Monitoring and evaluation (M&E) is critically important to track who is benefiting from adaptation investments and how, as well as to identify where inequities in access to opportunities, financial resources and other benefits exist.

Further Resources

Suggested Citation

NAP Global Network & UNFCCC. (2019). Toolkit for a gender-responsive process to formulate and implement National Adaptation Plans (NAPs). Dazé, A., and Church, C. (lead authors). Winnipeg: International Institute for Sustainable Development. Retrieved from www.napglobalnetwork.org